PHILIPPINES – Kaspersky Lab, INTERPOL, Europol and authorities from different countries have combined efforts to uncover the criminal plot behind an unprecedented cyberrobbery.

Up to one billion American dollars was stolen in about two years from financial institutions worldwide. The experts report that responsibility for the robbery rests with a multinational gang of cybercriminals from Russia, Ukraine and other parts of Europe, as well as from China.

The Carbanak criminal gang responsible for the cyberrobbery used techniques drawn from the arsenal of targeted attacks.

The plot marks the beginning of a new stage in the evolution of cybercriminal activity, where malicious users steal money directly from banks, and avoid targeting end users.

Since 2013, the criminals have attempted to attack up to 100 banks, e-payment systems and other financial institutions in around 30 countries.

The attacks remain active. According to Kaspersky Lab data, the Carbanak targets included financial organizations in Russia, USA, Germany, China, Ukraine, Canada, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Romania, France, Spain, Norway, India, the UK, Poland, Pakistan, Nepal, Morocco, Iceland, Ireland, Czech Republic, Switzerland, Brazil, Bulgaria, and Australia.

It is estimated that the largest sums were grabbed by hacking into banks and stealing up to ten million dollars in each raid.

On average, each bank robbery took between two and four months, from infecting the first computer at the bank’s corporate network to making off with the stolen money.

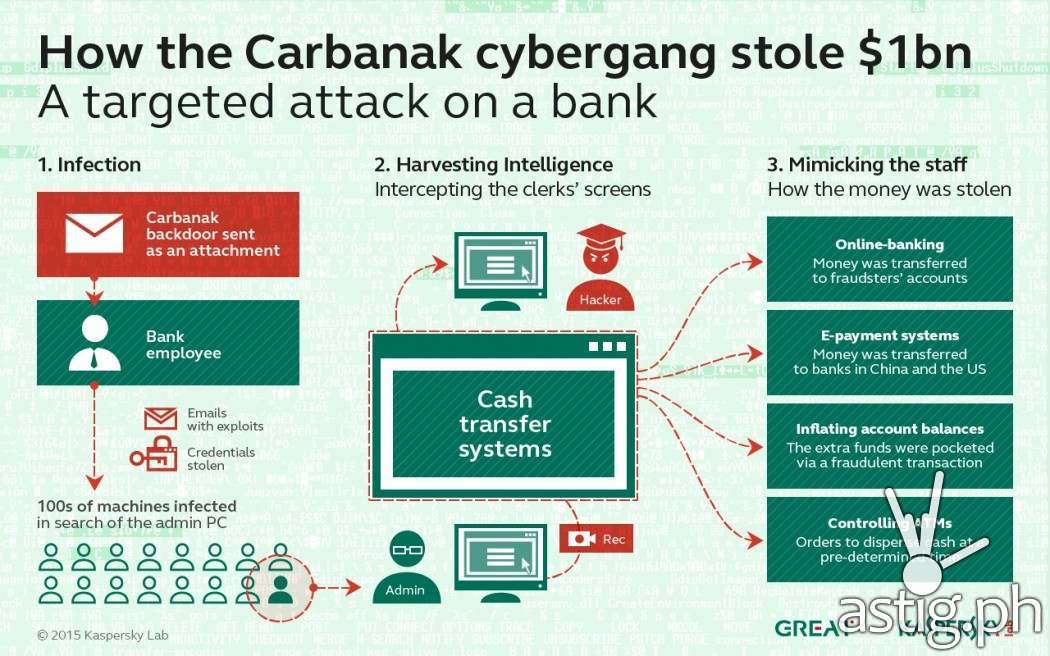

The cybercriminals began by gaining entry into an employee’s computer through spear phishing, infecting the victim with the Carbanak malware.

They were then able to jump into the internal network and track down administrators’ computers for video surveillance. This allowed them to see and record everything that happened on the screens of staff who serviced the cash transfer systems.

In this way the fraudsters got to know every last detail of the bank clerks’ work and were able to mimic staff activity in order to transfer money and cash out.

How the money was stolen

When the time came to cash in on their activities, the fraudsters used online banking or international e-payment systems to transfer money from the banks’ accounts to their own. In the second case the stolen money was deposited with banks in China or America. The experts do not rule out the possibility that other banks in other countries were used as receivers.

In other cases cybercriminals penetrated right into the very heart of the accounting systems, inflating account balances before pocketing the extra funds via a fraudulent transaction. For example: if an account has 1,000 dollars, the criminals change its value so it has 10,000 dollars and then transfer 9,000 to themselves. The account holder doesn’t suspect a problem because the original 1,000 dollars are still there.

In addition, the cyberthieves seized control of banks’ ATMs and ordered them to dispense cash at a pre-determined time. When the payment was due, one of the gang’s henchmen was waiting beside the machine to collect the ‘voluntary’ payment.

“These bank heists were surprising because it made no difference to the criminals what software the banks were using. So, even if its software is unique, a bank cannot get complacent. The attackers didn’t even need to hack into the banks’ services: once they got into the network, they learned how to hide their malicious plot behind legitimate actions. It was a very slick and professional cyber-robbery,” said Sergey Golovanov, Principal Security Researcher at Kaspersky Lab’s Global Research and Analysis Team.

“These attacks again underline the fact that criminals will exploit any vulnerability in any system. It also highlights the fact that no sector can consider itself immune to attack and must constantly address their security procedures. Identifying new trends in cybercrime is one of the key areas where INTERPOL works with Kaspersky Lab in order to help both the public and private sectors better protect themselves from these evolving threats,” said Sanjay Virmani, Director of the INTERPOL Digital Crime Centre.

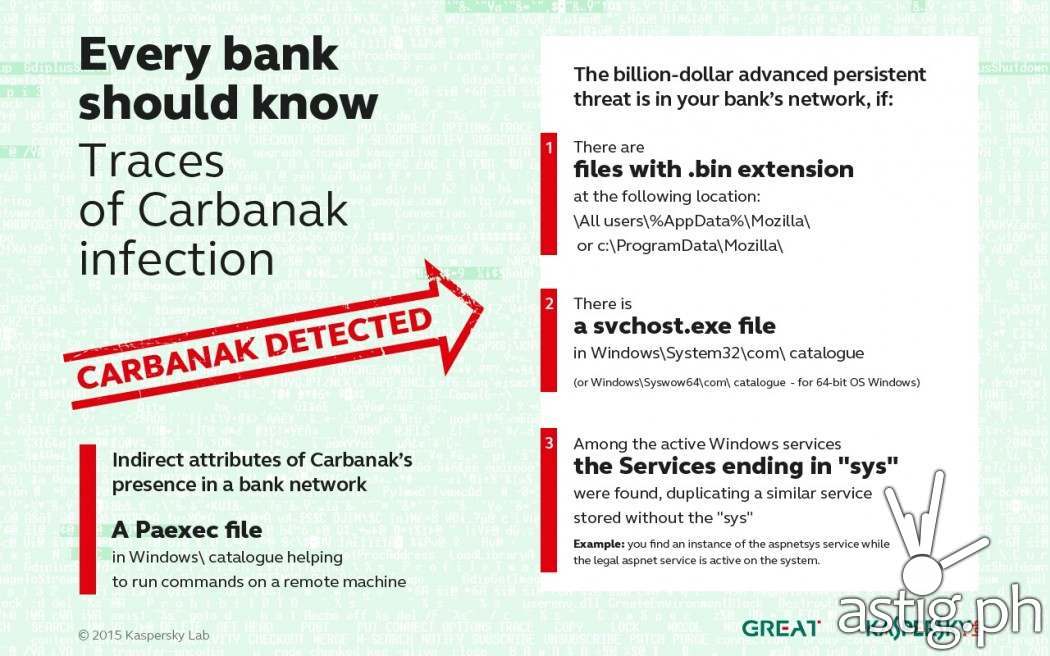

Kaspersky Lab urges all financial organizations to carefully scan their networks for the presence of Carbanak and, if detected, report the intrusion to law enforcement.

To learn more about the “Carbanak” operation, read the blog post available at Securelist.com.